You might be wondering why we’re interested in slime, or what we mean by sequencing, so read on to find out!

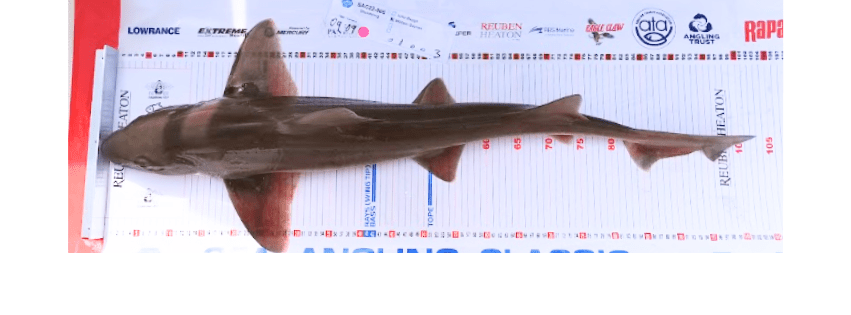

One part of our project involves identifying smoothhounds and skates. These can be tricky to identify by looking at them because their colourings can be variable. In smoothhounds for example, common smoothhounds never have spots, but starry smoothhounds sometimes do and sometimes don’t, so if you catch one without spots you don’t know what species it is. Because of this we want to identify them using their DNA.

Above is a picture of a smoothhound with no visible spots: Is it a Common Smoothhound? Or is it a Starry Smoothhound with no spots??

DNA is fantastic for identifying species because it doesn’t rely on us looking at colours, shapes or sizes to work out what species we’ve got. All species have a region in their DNA called a barcode and this barcode is different for every single species, so if you can read what the barcode is you can work out what species you have!

Collecting good quality DNA normally requires taking a blood or skin sample, but we wanted to collect DNA in a way that isn’t damaging to the fish. This is why we get excited about slime! Rays and sharks have a slime, or mucus, layer covering their bodies and this traps DNA. We wanted to collect some of this mucus, so we recently tried a method using a kitchen sponge scourer. This method has even been used underwater on sleeping rays without waking them up! All it takes is 3 short wipes with the scourer to collect enough mucus to send off for analysis, so it’s a quick process and then the shark or ray can be released.

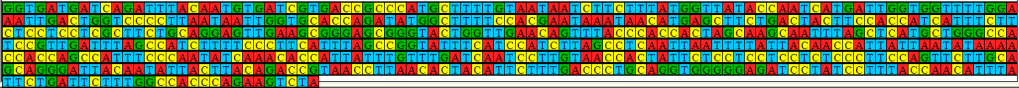

We send the samples to a genetics company who separate the DNA from the mucus. The amount of DNA in the sample will be so tiny that we need to produce multiple identical copies of it before we can send it to the next stage. Things called primers are added to the sample to ensure that only the barcode region gets replicated. Once we’ve got thousands of copies of the barcode region we can send the sample off to be sequenced.

Sequencing is where a machine reads the barcode and tells us the sequence, which is made up of 4 letters: A, T, C and G. We can then search for the unique barcode in an online database to see what species it is. In our first trial of this method we swabbed what we assumed was a starry smoothhound, and the genetic barcode confirmed this was correct!

We’ll be doing lots of DNA swabbing over the summer, so keep an eye on the blog or click ‘subscribe’ to keep up to date with our work.

A photo of our Senior Research Associate, Christina, releasing the smoothhound back into the sea.

If you’d like to hear more about our research, please do follow us:

Facebook: Competitive Angling as a Scientific Tool – Portsmouth Uni Marine Biology

Instagram: cast_uop

Or subscribe on our website

Leave a comment